Ruminants are artiodactyl characterised by their possession of stomachs with four compartments. They are said to have four “stomachs” which is technically untrue as they have only one stomach but divided into four parts: the rumen, reticulum, omasum and abomasum. Nearly 200 wild ruminant species exist including cows, goats, deer, giraffes, moose and elk.

|

| A ruminant with the digestive tract shown. Retrieved from https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/5f/a0/48/5fa048c43a9e7a5af3f86630e4e24939.jpg |

Origin of the Ruminants Stomach

When the first ruminant groups emerged, they were rabbit sized (< 5kg; Hackmann & Spain, 2010). Their skull and dental morphology were optimal for consuming fruits and insects. This shows that the first ruminants were small, forest welling omnivores (Webb, 1998b). The first ruminants did not have a functional rumen until about 40ma as indicated by dental morphology and molecular techniques (Hackmann & Spain, 2010). At about 18 to 23 ma, new families of ruminants evolved with these families having masses of 20kg to 40kg. The new families ate primarily leaves as evidenced by dental wear (Hackmann & Spain, 2010). By about 5 to 11 ma, grasslands had expanded and some species began including more grass in their diets leading to the development of more complex stomach to help in the digestion of the grasses.

Structure and Histology of the Ruminant’s Stomach

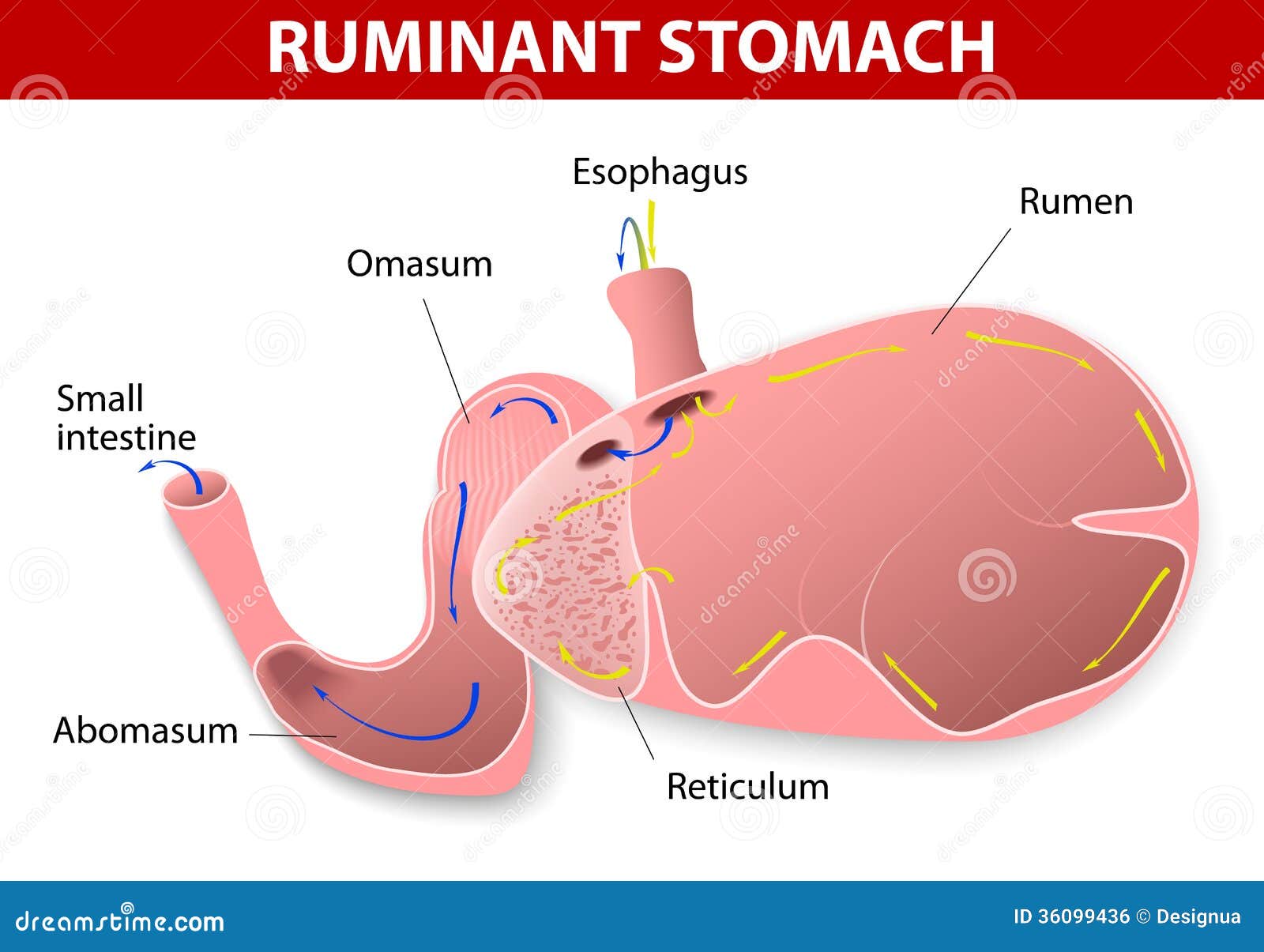

The ruminant’s stomach has four compartments: the rumen, reticulum, omasum and abomasum.

|

| https://thumbs.dreamstime.com/z/ruminant-stomach-species-have-one-divided-four-compartments-rumen-reticulum-omasum-abomasum-36099436.jpg |

| The ruminant rumen from veterinary histology |

Reticulum: this is the most cranial part of the stomach and food and sometimes objects drops in here first. The reticulum consists of mucosa, submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa. The reticular walls are lined with mucous membranes that are organized in folds (laminae) to form a honeycomb pattern. On the laminae are short conical projections called papillae. The lamina epithelial is keratinized stratified squamous epithelim. Contractions of the honeycomb cells, with the purse-string action of the smooth muscle strands, help the mechanical digestion of the ingesta. The reticulum contracts to slosh the ingesta between itself and the rumen (Kardong, 2002).

|

| reticulum, uploaded from veterinary histology |

Omasum: this is the third portion of the system that ingesta pass through in the ruminant. It is spherical in shape and located to the right of the rumen and reticulum, as well as being the smallest of the four compartments. The inside walls are covered in muscular laminae that are studded with short papillae. The mucosa and portions of muscularis mucosae form parallel folds that resemble pages of an open book. The mucosal surface is covered by stratified squamous epithelium. The core of the laminae are quite characteristic with three layers of smooth muscle. Extending upward from the muscularis mucosae are fibers that form the two outer layers. The orientation of the muscle cells is parallel to the free edge of the laminae. Sandwiched between these two layers is a single inner layer of smooth muscle. This is derived from the muscularis externa and the fibers are perpendicular to those of the outer layers. The omasum operates like a two phase machine. First, there is relaxation of the muscular walls which aspirates fluids and fine particles from reticulum into the omasum (Kardong, 2002). Second, the omasum contracts to force the digesta into the abomasum. The omasum absorbs volatile fatty acids, ammonia and water and at the same time separates the fermenting content of the rumen and reticulum from the highly acidic content of the abomasum (Kardong, 2002).

| omasum from veterinary histology |

Abomasum: this is the fundic part of the stomach in which further digestion occurs before digesta pass to the intestine. It is the glandular portion of the ruminant stomach and its histology is highly similar to that of monogastric animals. The lumen of the glandular stomach is lined with simple columnar mucus-secreting epithelium. The mucosa is thrown up into longitudinal folds called rugae which stretch flat as the stomach distends. The lamina propria is a loose connective tissue layer rich in capillaries and lymphoid cells and is entirely occupied by glands, the gastric glands (Kardong, 2002). The abomasum produces hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes, such as pepsin (breaks down proteins), and receives digestive enzymes secreted from the pancreas, such as pancreatic lipase (breaks down fats). These secretions help prepare proteins for absorption in the intestines. The pH in the abomasum generally ranges from 3.5 to 4.0. The chief cells in the abomasum secrete mucous to protect the abomasal wall from acid damage (Kardong, 2002).

Pathology of the stomach

- Ruminal parakeratosis: is a disease of cattle and sheep characterized by hardening and enlargement of the papillae of the rumen. It is most common in animals fed a high-concentrate ration during the finishing period. Affected papillae contain excessive layers of keratinized epithelial cells, particles of food, and bacteria. Ruminal parakeratosis may be prevented by finishing animals on rations that contain unground ingredients in the proportion of 1 part roughage to 3 parts concentrate (Merck Manuals, 2015).

- Simple Gastritis: bloating is a form of gastritis in ruminants. It involves the inflammation of the rumenoreticulum with the gases of fermentation, either in the form of a persistent foam mixed with the ruminal contents, called primary or frothy bloat, or in the form of free gas separated from the ingesta, called secondary or free-gas bloat (Merck Manuals, 2015).

- Omasitis; Inflammation of the Omasum. This condition may be brought about by an irritant in the food being compressed between the leaves of the omasum, and thus brought into close contact with its mucous membrane. This organ, however, appears to be very resist ant to irritants, and it is not easily inflamed. Omasitis may occur as a result of poisoning, with such irritants as yew, rhododendron, bracken, and arsenic (Book upstairs, 2011).

References

Books Upstirs (2011). Diseases of the stomach in ruminants. Retrieved from http://www.booksupstairs.com/Veterinary-Medicine/Diseases-of-the-Stomach.html

BVetMed1 (18 March 2013). Ruminant GIT Physiology and Histology. Retrieved from http://bvetmed1.blogspot.ca/2013/03/ruminant-git-physiology-and-histology.html

Kardong, K. V. (2002). Vertebrates Comparative Anatomy, Function and Evolution. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Kwan, P. (n.d). Digestive system II: esophagus and Stomach. Retrieved from http://ocw.tufts.edu/data/4/531950.pdf

The Beef Site (22 August 2009). Understanding the Ruminant’s Animal’s Digestive System. Retrieved from http://www.thebeefsite.com/articles/2095/understanding-the-ruminant-animals-digestive-system/

The Merck Vertinary Manual (2015). Bloat in ruminants. Retrieved from http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/digestive_system/diseases_of_the_ruminant_forestomach/bloat_in_ruminants.html

Veterinary Histology (2006), accessed 24 October 2016, http://www.vetmansoura.com/Histology/Digestive/Digestive1.html

webb, S. D. (1998b). Hornless ruminants. Evolution of Tertiary mammals of North America, 1 (463-476).