Let’s Ruminate on it

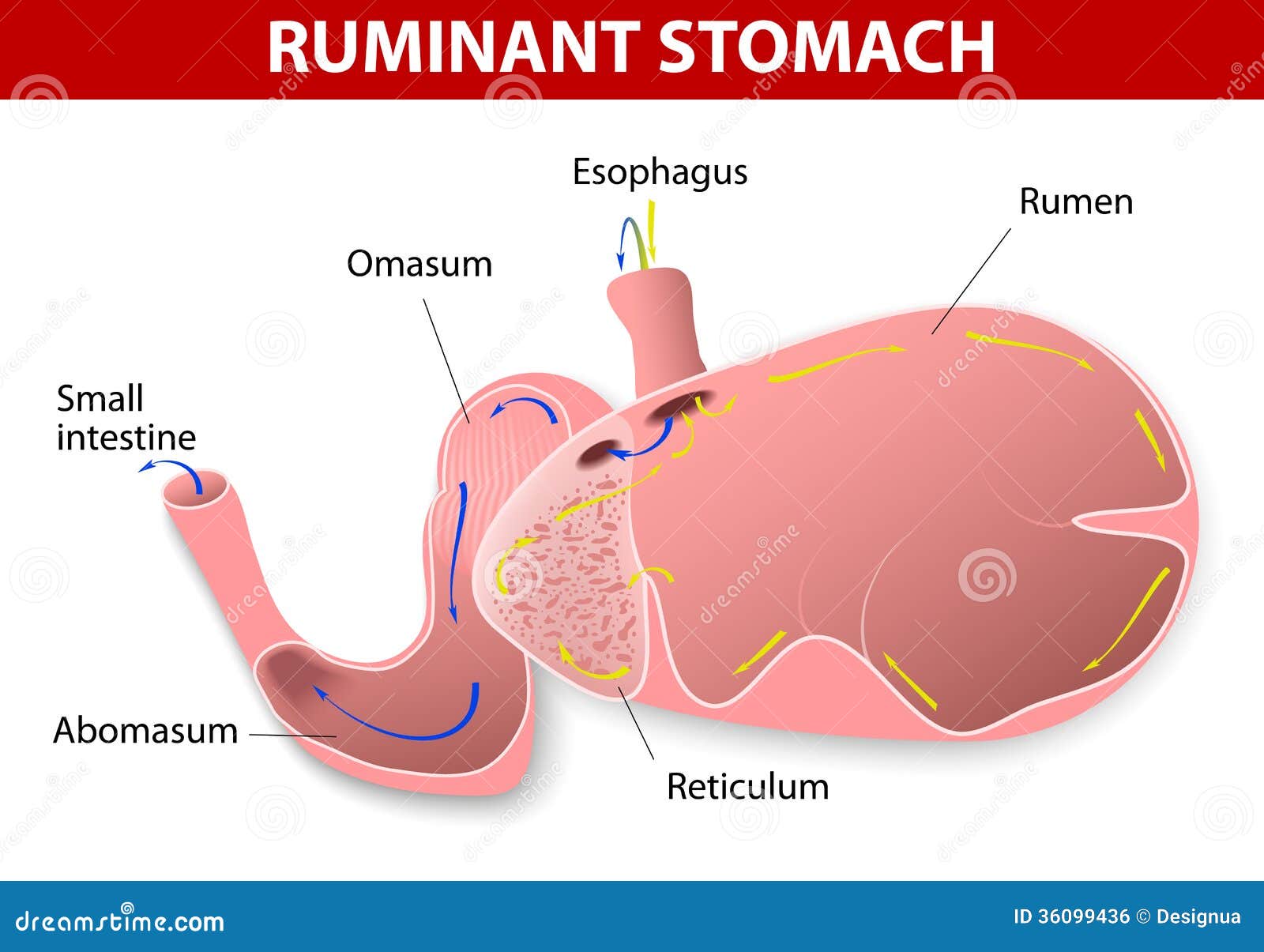

Ruminants are artiodactyl characterised by their possession

of stomachs with four compartments. They are said to have four “stomachs” which

is technically untrue as they have only one stomach but divided into four

parts: the rumen, reticulum, omasum and abomasum. Nearly 200 wild ruminant

species exist including cows, goats, deer, giraffes, moose and elk.

Origin of the

Ruminants Stomach

When the first ruminant groups emerged, they were rabbit

sized (< 5kg; Hackmann & Spain, 2010). Their skull and dental morphology

were optimal for consuming fruits and insects. This shows that the first

ruminants were small, forest welling omnivores (Webb, 1998b). The first

ruminants did not have a functional rumen until about 40ma as indicated by

dental morphology and molecular techniques (Hackmann & Spain, 2010). At about

18 to 23 ma, new families of ruminants evolved with these families having masses

of 20kg to 40kg. The new families ate primarily leaves as evidenced by dental

wear (Hackmann & Spain, 2010). By about 5 to 11 ma, grasslands had expanded

and some species began including more grass in their diets leading to the

development of more complex stomach to help in the digestion of the grasses.

Structure and

Histology of the Ruminant’s Stomach

The ruminant’s stomach has four compartments: the rumen,

reticulum, omasum and abomasum.

Reticulum: this

is the most cranial part of the stomach and food and sometimes objects drops in

here first. The reticulum consists of mucosa, submucosa, tunica muscularis and

serosa. The reticular walls are lined with mucous membranes that are organized

in folds (laminae) to form a honeycomb pattern. On the laminae are short

conical projections called papillae. The lamina epithelial is keratinized

stratified squamous epithelim. Contractions of the honeycomb cells, with the

purse-string action of the smooth muscle strands, help the mechanical digestion

of the ingesta. The reticulum contracts to slosh the ingesta between itself and

the rumen (Kardong, 2002).

Omasum: this is

the third portion of the system that ingesta pass through in the ruminant. It

is spherical in shape and located to the right of the rumen and reticulum, as

well as being the smallest of the four compartments. The inside walls are

covered in muscular laminae that are studded with short papillae. The mucosa

and portions of muscularis mucosae form parallel folds that resemble pages of

an open book. The mucosal surface is covered by stratified squamous epithelium.

The core of the laminae are quite characteristic with three layers of smooth

muscle. Extending upward from the muscularis mucosae are fibers that form the

two outer layers. The orientation of the muscle cells is parallel to the free

edge of the laminae. Sandwiched between these two layers is a single inner

layer of smooth muscle. This is derived from the muscularis externa and the

fibers are perpendicular to those of the outer layers. The omasum operates like

a two phase machine. First, there is relaxation of the muscular walls which aspirates

fluids and fine particles from reticulum into the omasum (Kardong, 2002). Second,

the omasum contracts to force the digesta into the abomasum. The omasum absorbs

volatile fatty acids, ammonia and water and at the same time separates the

fermenting content of the rumen and reticulum from the highly acidic content of

the abomasum (Kardong, 2002).

Abomasum: this is

the fundic part of the stomach in which further digestion occurs before digesta

pass to the intestine. It is the glandular portion of the ruminant stomach and

its histology is highly similar to that of monogastric animals. The lumen of

the glandular stomach is lined with simple columnar mucus-secreting epithelium. The mucosa is thrown up into longitudinal folds called rugae which stretch flat as the stomach

distends. The lamina propria is a loose connective tissue layer

rich in capillaries and lymphoid cells and is entirely occupied by glands, the gastric glands (Kardong, 2002). The

abomasum produces hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes, such as pepsin

(breaks down proteins), and receives digestive enzymes secreted from the

pancreas, such as pancreatic lipase (breaks down fats). These secretions help

prepare proteins for absorption in the intestines. The pH in the abomasum

generally ranges from 3.5 to 4.0. The chief cells in the abomasum secrete

mucous to protect the abomasal wall from acid damage (Kardong, 2002).

Development

of the Ruminant Stomach

No comments:

Post a Comment